and art-agenda editorial is now e-flux Criticism

The Lebanese artist Abdel Hamid Baalbaki painted four major murals in his lifetime. Baalbaki called them murals, but in reality they were large-scale oil or acrylic paintings on canvas that strived for monumentality. They combine references to historical events, religious rituals, and performative reenactments. Though aware of the Mexican muralists David Alfaro Siqueiros and Diego Rivera when he painted these works in the 1970s, Baalbaki was inspired by the Iraqi modernists Jewad Selim and Kadhim Hayder, who had turned to archeology and mythology, a decade earlier, to form the elements of a new national culture.

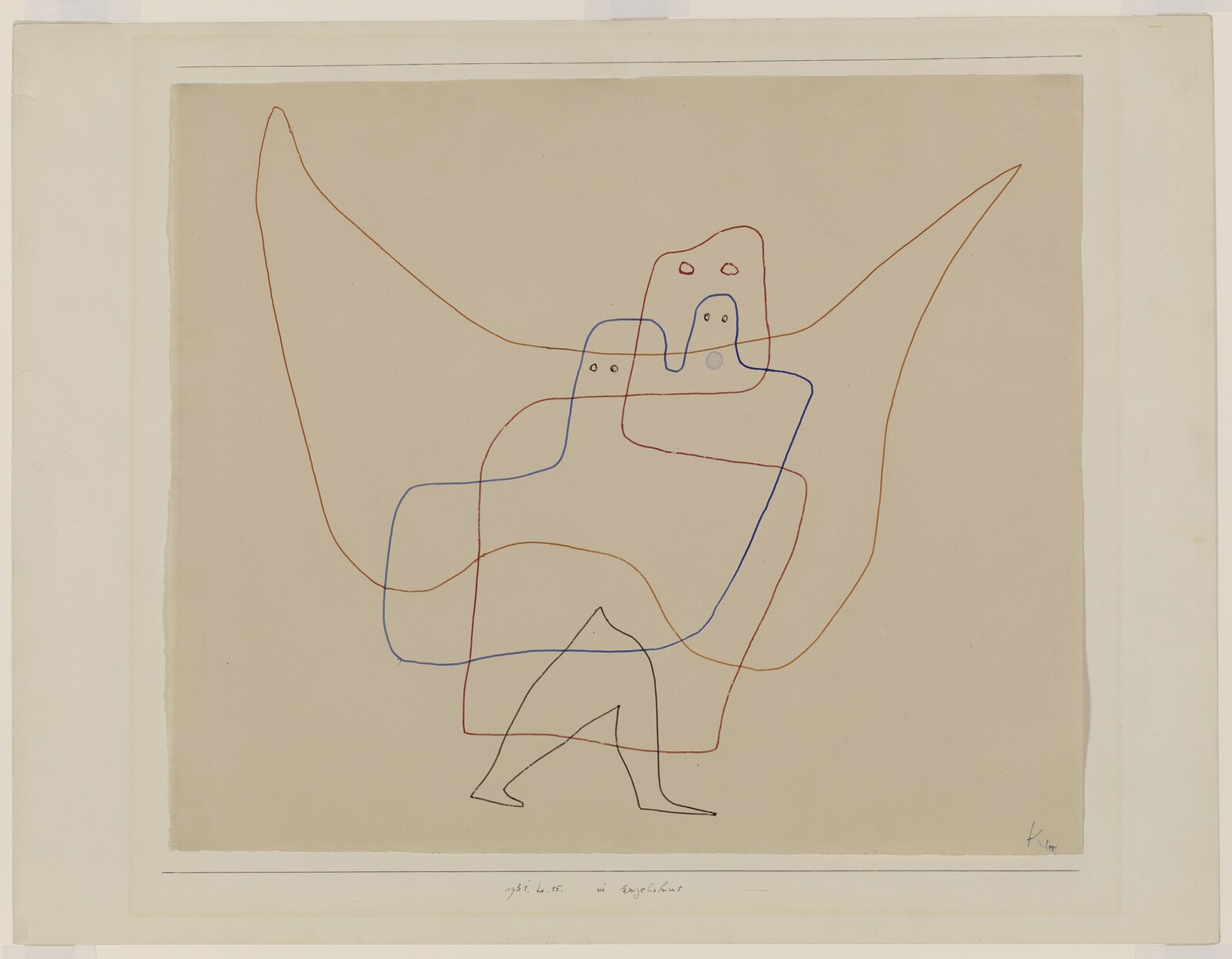

Rather than seeking out works of art that reinforce the dominant narrative of the present, the art historian—and his short-sighted accomplice, the critic—might instead be on the lookout for those that resist classification, that cannot be systematized, that are irrepressible because they are vital (Warburg called these recurring figures nachleben, or “afterlives”). And for those disorderly, chaotic, and dangerous irruptions of unstructured feeling that might explain the dissolution of old certainties and offer a glimpse of what is to come.

Noting the cultural and scientific precedents—from material innovation to discoveries in molecular structure—that have fostered new approaches to architecture and town-planning, Stalder’s book explores how postwar architects began to see buildings in terms of totalizing environments. Open-plan and glass promoted transparency, and sunlight and breeze were considered as important as bricks and mortar. What was at stake was “the control of a multilayered visual, climatic, spatial environment”: or, as László Moholy-Nagy put it, why should one “live between stone walls when one could live under the blue sky between green trees with all the advantages of perfect insulation?”

Ohtsubo’s Willow Rain (2025) is an environment made of 800 basket willow branches suspended from the ceiling. It creates a portal composed of thin, long strips of dried plants that, inverting the natural order of vegetal growth up from the ground, invites viewers to look upwards, both to the suspended plants and to the hypnotizing shadows they cast upon the walls. In the surrounding spaces, Oldham’s Dateline (2025) consists of Medjool dates strung on lightning rods, merging minimalist aesthetics with reference to a staple Middle Eastern food.

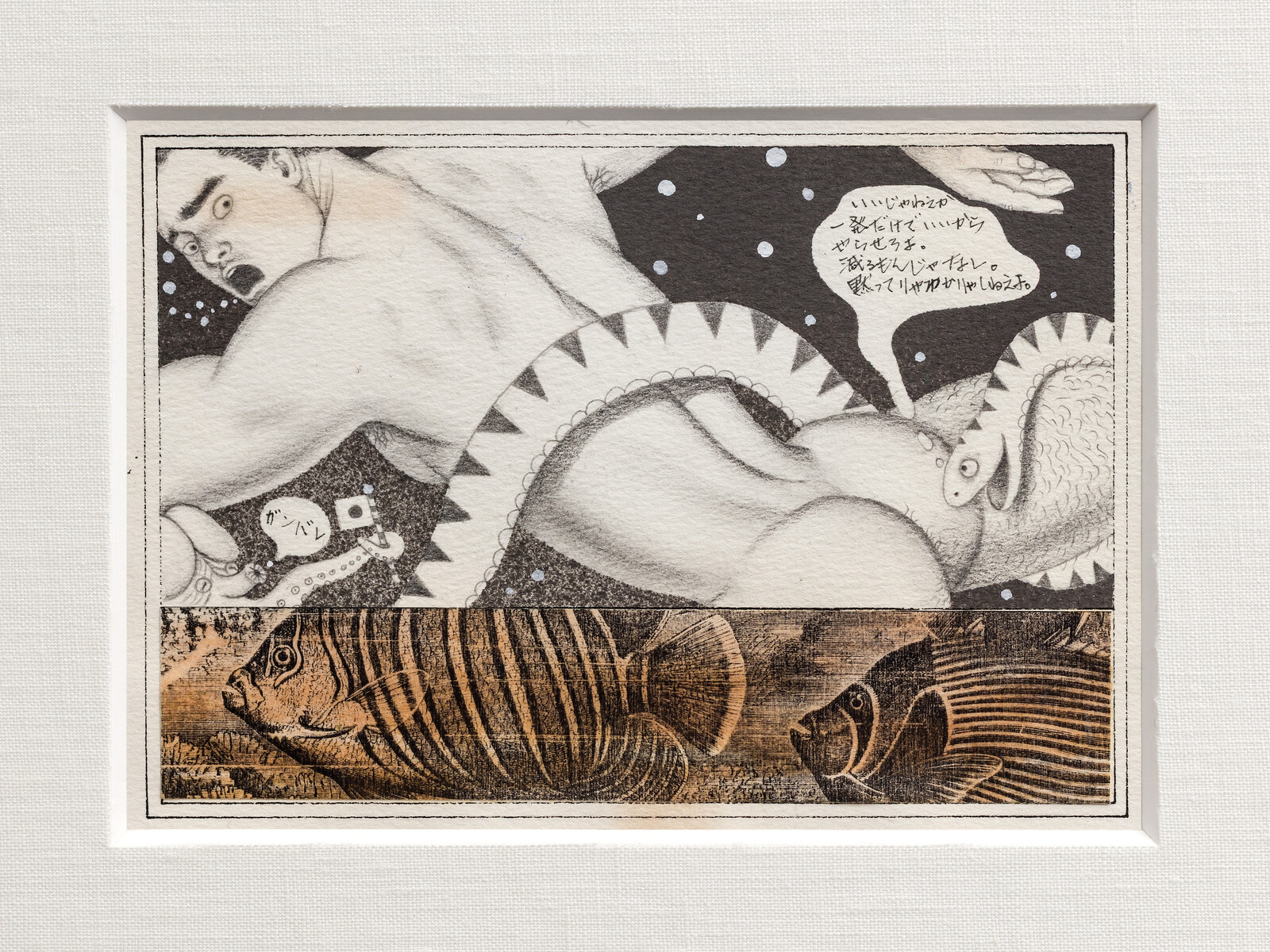

Hasegawa named as key influences Tom of Finland and Go Mishima, the latter renowned for his illustrations of yakuza-tattooed men. But what distinguishes Hasegawa is the limitlessness of his world—where men can fuck each other without societal, national, or even species constraints. While he often explored Japanese tropes—kabuki, shunga—this exhibition emphasizes the perviousness of his view of culture and ethnicity.

An artist told me that, when the full-scale invasion occurred, in February 2022, the natural reaction was for him and his peers to make “posters,” by which he meant works of undisguised propaganda. Since then, however, as war has permeated the atmosphere (some of the youngest artists in the prize have only been exhibiting properly for three years, meaning they’ve never had a career in peacetime), an appetite has grown for more introspective stories.