and art-agenda editorial is now e-flux Criticism

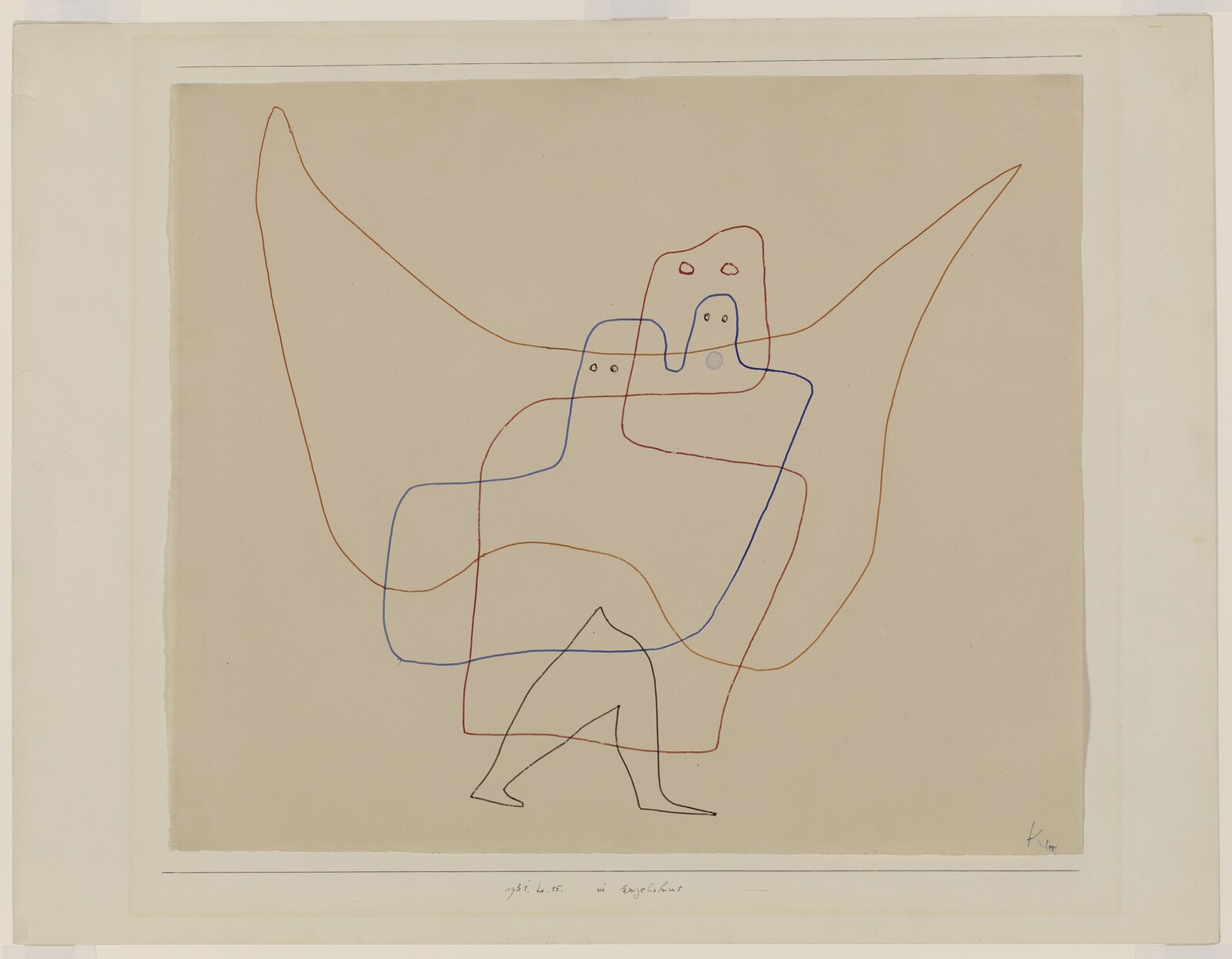

Rather than seeking out works of art that reinforce the dominant narrative of the present, the art historian—and his short-sighted accomplice, the critic—might instead be on the lookout for those that resist classification, that cannot be systematized, that are irrepressible because they are vital (Warburg called these recurring figures nachleben, or “afterlives”). And for those disorderly, chaotic, and dangerous irruptions of unstructured feeling that might explain the dissolution of old certainties and offer a glimpse of what is to come.

Noting the cultural and scientific precedents—from material innovation to discoveries in molecular structure—that have fostered new approaches to architecture and town-planning, Stalder’s book explores how postwar architects began to see buildings in terms of totalizing environments. Open-plan and glass promoted transparency, and sunlight and breeze were considered as important as bricks and mortar. What was at stake was “the control of a multilayered visual, climatic, spatial environment”: or, as László Moholy-Nagy put it, why should one “live between stone walls when one could live under the blue sky between green trees with all the advantages of perfect insulation?”

Ohtsubo’s Willow Rain (2025) is an environment made of 800 basket willow branches suspended from the ceiling. It creates a portal composed of thin, long strips of dried plants that, inverting the natural order of vegetal growth up from the ground, invites viewers to look upwards, both to the suspended plants and to the hypnotizing shadows they cast upon the walls. In the surrounding spaces, Oldham’s Dateline (2025) consists of Medjool dates strung on lightning rods, merging minimalist aesthetics with reference to a staple Middle Eastern food.

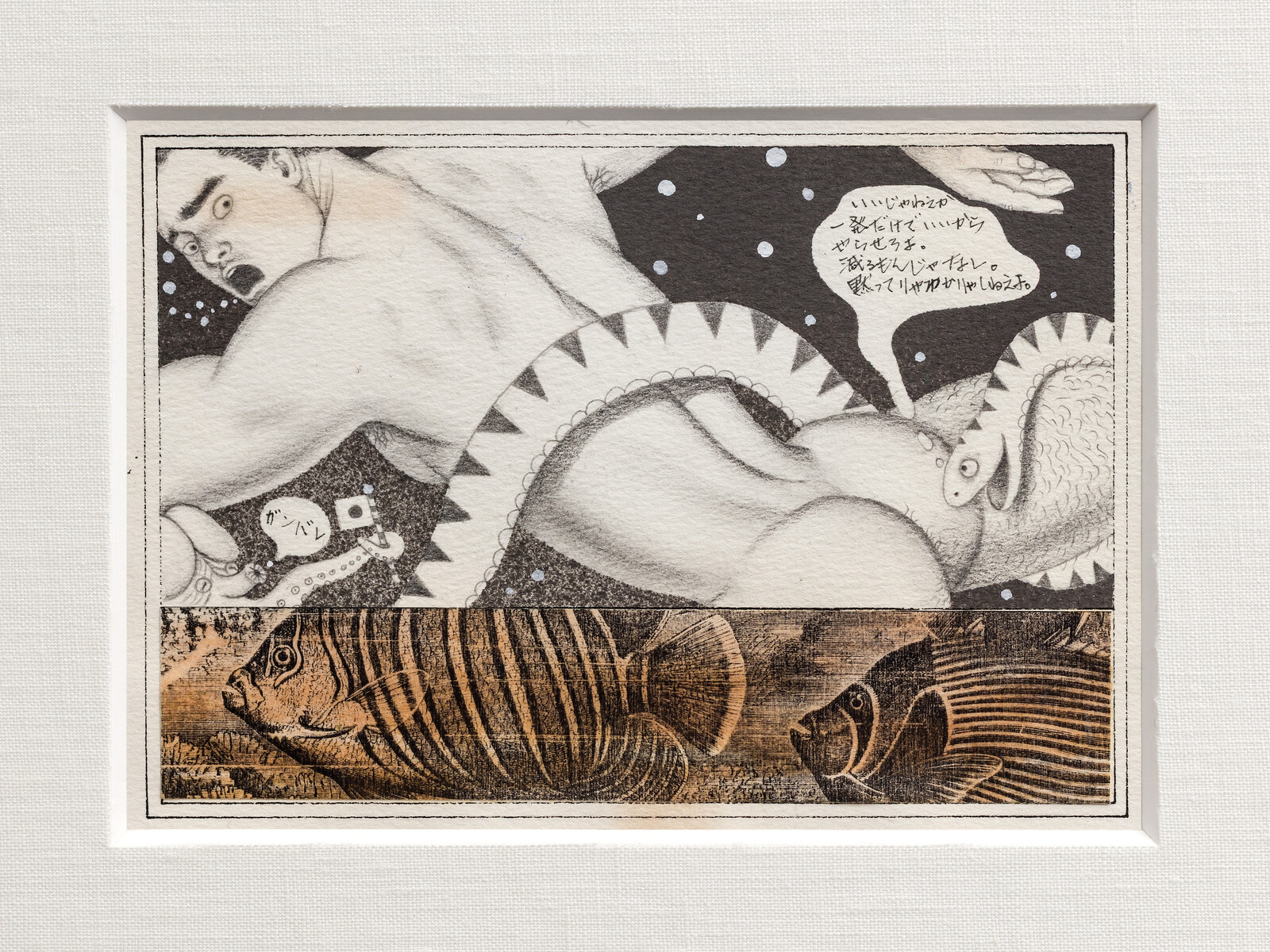

Hasegawa named as key influences Tom of Finland and Go Mishima, the latter renowned for his illustrations of yakuza-tattooed men. But what distinguishes Hasegawa is the limitlessness of his world—where men can fuck each other without societal, national, or even species constraints. While he often explored Japanese tropes—kabuki, shunga—this exhibition emphasizes the perviousness of his view of culture and ethnicity.

An artist told me that, when the full-scale invasion occurred, in February 2022, the natural reaction was for him and his peers to make “posters,” by which he meant works of undisguised propaganda. Since then, however, as war has permeated the atmosphere (some of the youngest artists in the prize have only been exhibiting properly for three years, meaning they’ve never had a career in peacetime), an appetite has grown for more introspective stories.

One surprising legacy of the United States’ public diplomacy across Southeast Asia during the Cold War is an eighteen-minute film featuring dialect and music indigenous to Thailand’s northeast region. Produced by the United States Information Service (USIS), The Community Development Worker (1963) pairs black-and-white 16mm footage of the smartly dressed titular subject touring a dusty village on foot to a soundtrack of jaunty, laudatory songs.

Industry Muscle