and art-agenda editorial is now e-flux Criticism

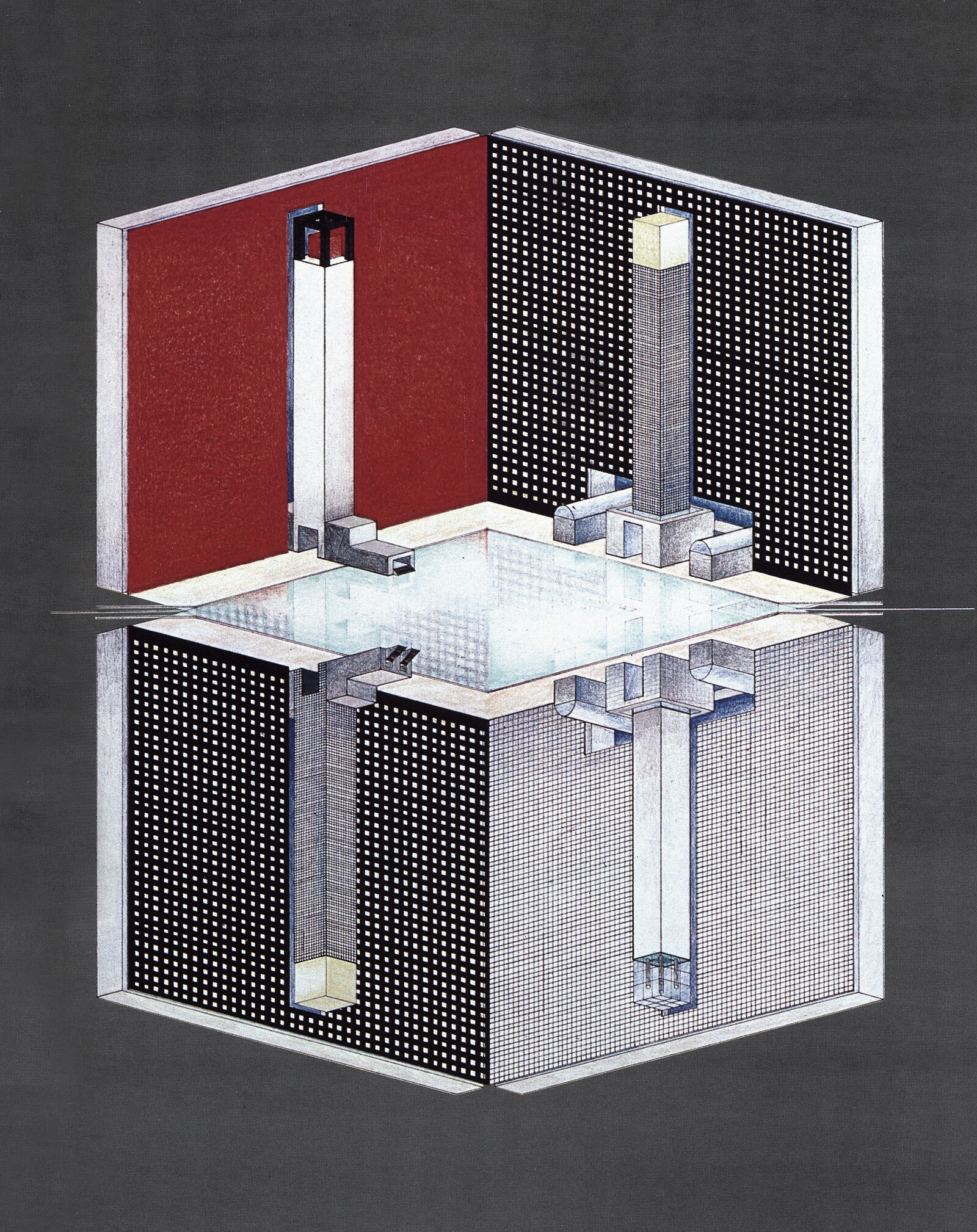

Interieur as Idea

New and Old Friends

In Hawaiian, nō is as an intensifying particle akin to “very” or “strongly” which, when glossed in English, reads as a statement of negation. Curators Noelle M.K.Y. Kahanu, Wassan Al-Khudhairi, and Binna Choi thereby juxtapose understandings of aloha as love, generosity, and reciprocity against the possibilities created by defiance and refusal. They urge their audience to renew the potency of a word routinely taken for granted by Hawaiʻi residents and tourists alike, framing Hawaiʻi as a site where aloha is regenerated through artistic practices beyond its dereliction at the hands of a militouristic occupying state.

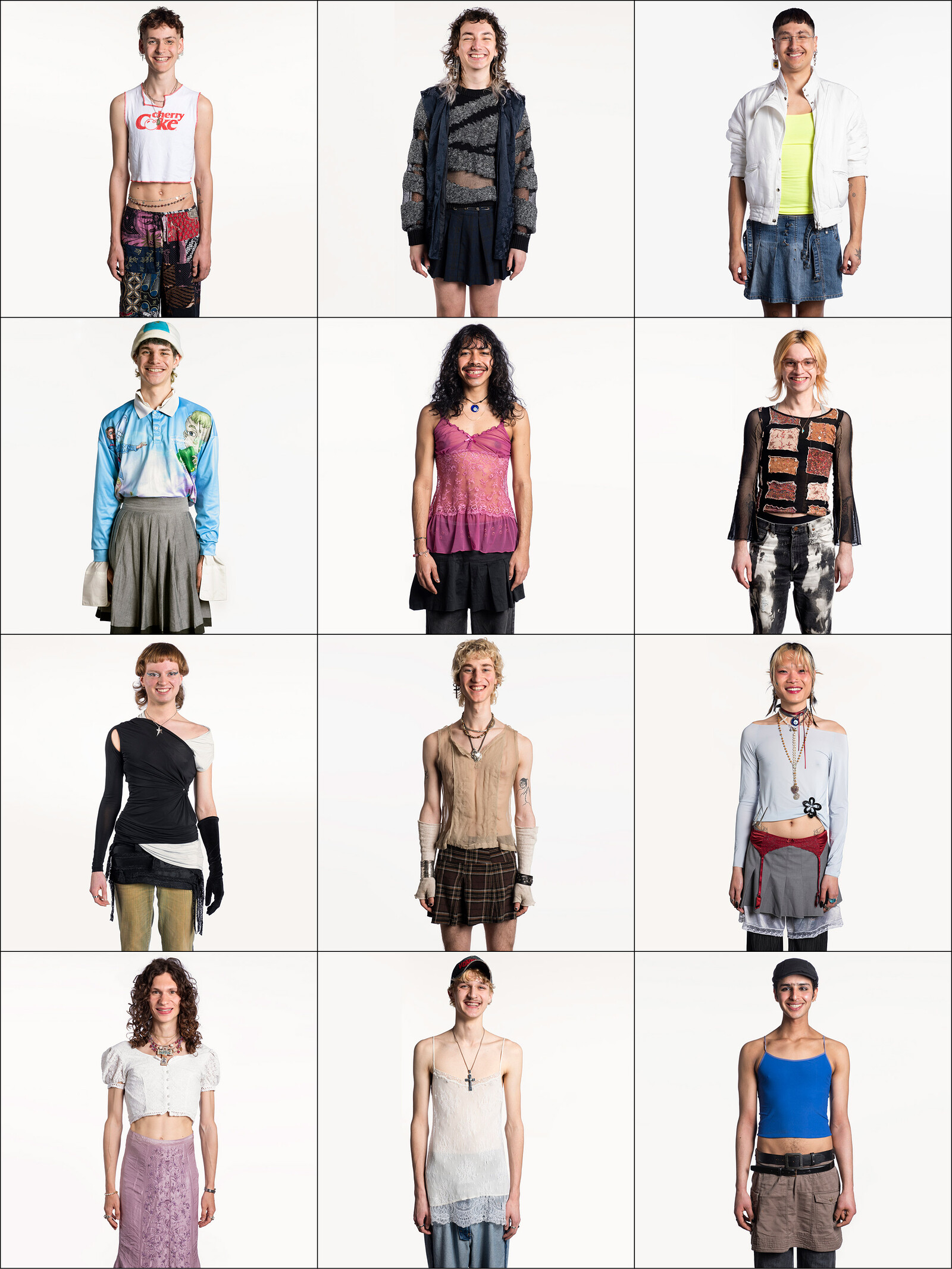

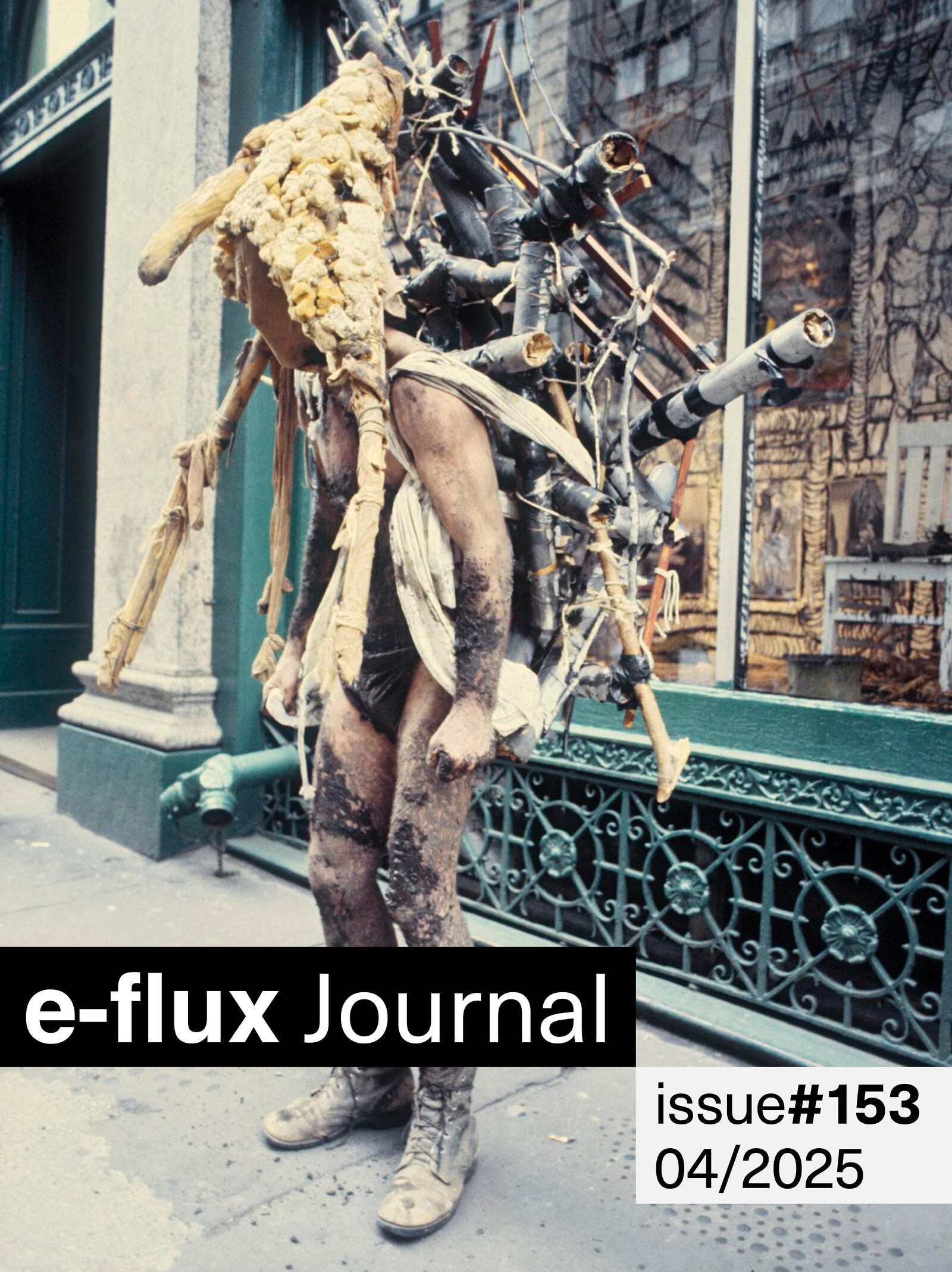

Amy O’Neill unpacks what the carnivalesque means today by uniting themes of production and performance, celebration and corruption. Installed near the entrance is STRAW MAN Vestment (all works 2025), one of three works which isolate Goya’s limp doll. Made of quilt tops and digitally printed fabric, O’Neill’s piece transforms the tortured figure into a prêt-à-porter object. The garment anchors the show, allowing the sightlines and angles that the artist creates around it to feel carefully measured.

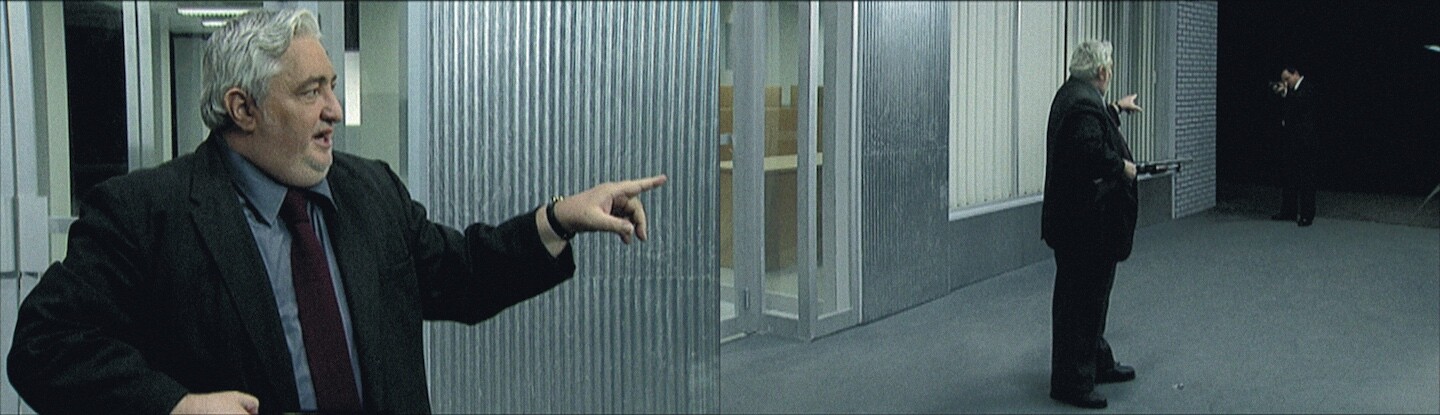

The gray skyscraper-fantasia of La Défense emerges as a synecdoche for the vampiric properties of corporate capitalism everywhere, even while the films remain local to the racialized neoliberal logics of the French capital: the arch was one of Socialist president François Mitterrand’s “Grands Projets,” and the business quarter’s construction from the late fifties onwards precipitated the displacement of predominantly Arab communities.

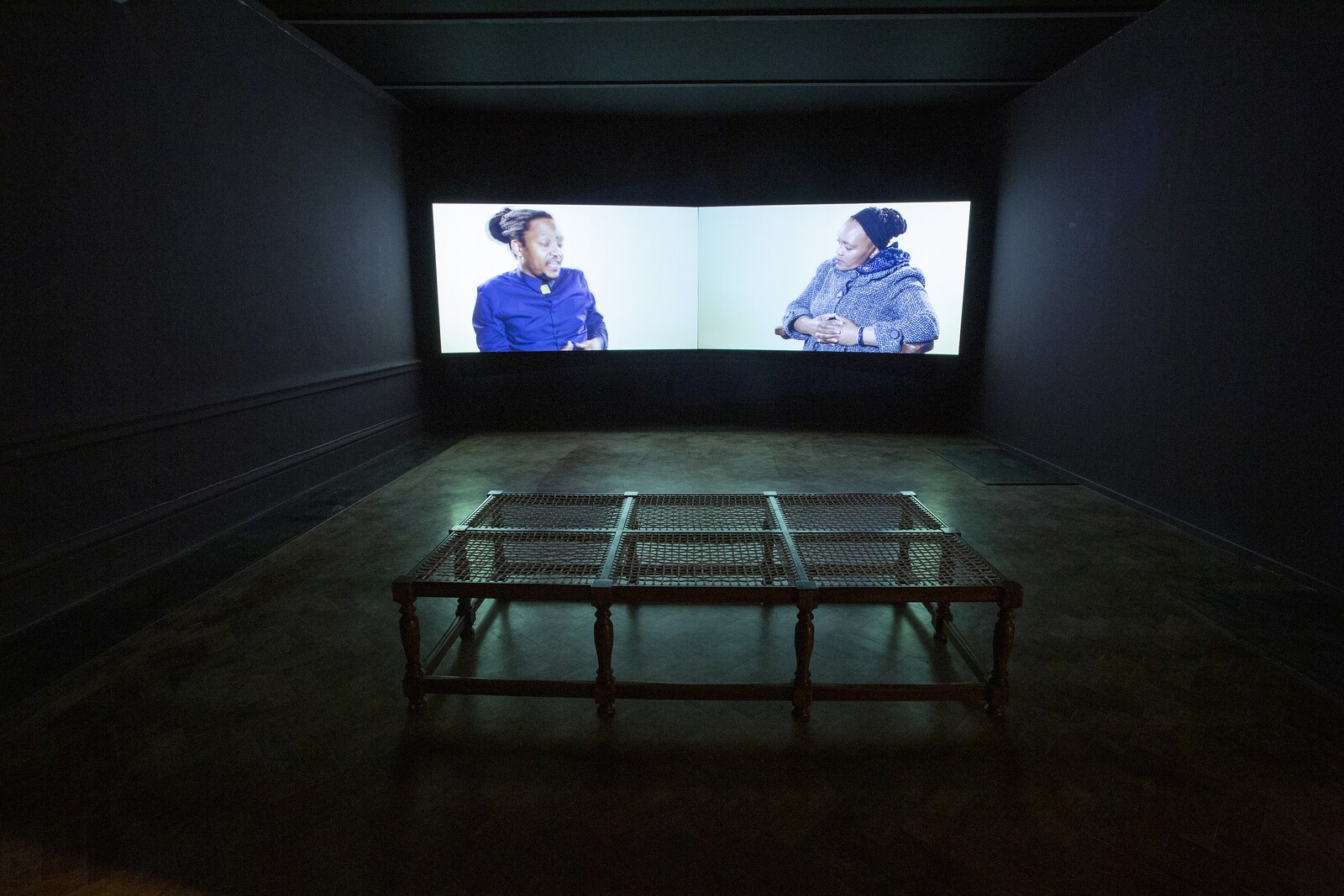

Williamson’s dream was to be a journalist, and photographs, photocopies, interviews are the methods and media to which she has regularly returned. The video work from which the retrospective borrows its title, There’s something I must tell you (2013), records conversations between freedom fighters and their daughters and granddaughters, while It’s a pleasure to meet you (2016) and That particular morning (2019) see the descendants of assassinated activists sharing stories of inherited trauma. A journalistic sensibility—to bear witness, to disseminate, to resist, against all odds, the amnesia of the next-thing—is at work.

The Lebanese artist Abdel Hamid Baalbaki painted four major murals in his lifetime. Baalbaki called them murals, but in reality they were large-scale oil or acrylic paintings on canvas that strived for monumentality. They combine references to historical events, religious rituals, and performative reenactments. Though aware of the Mexican muralists David Alfaro Siqueiros and Diego Rivera when he painted these works in the 1970s, Baalbaki was inspired by the Iraqi modernists Jewad Selim and Kadhim Hayder, who had turned to archeology and mythology, a decade earlier, to form the elements of a new national culture.

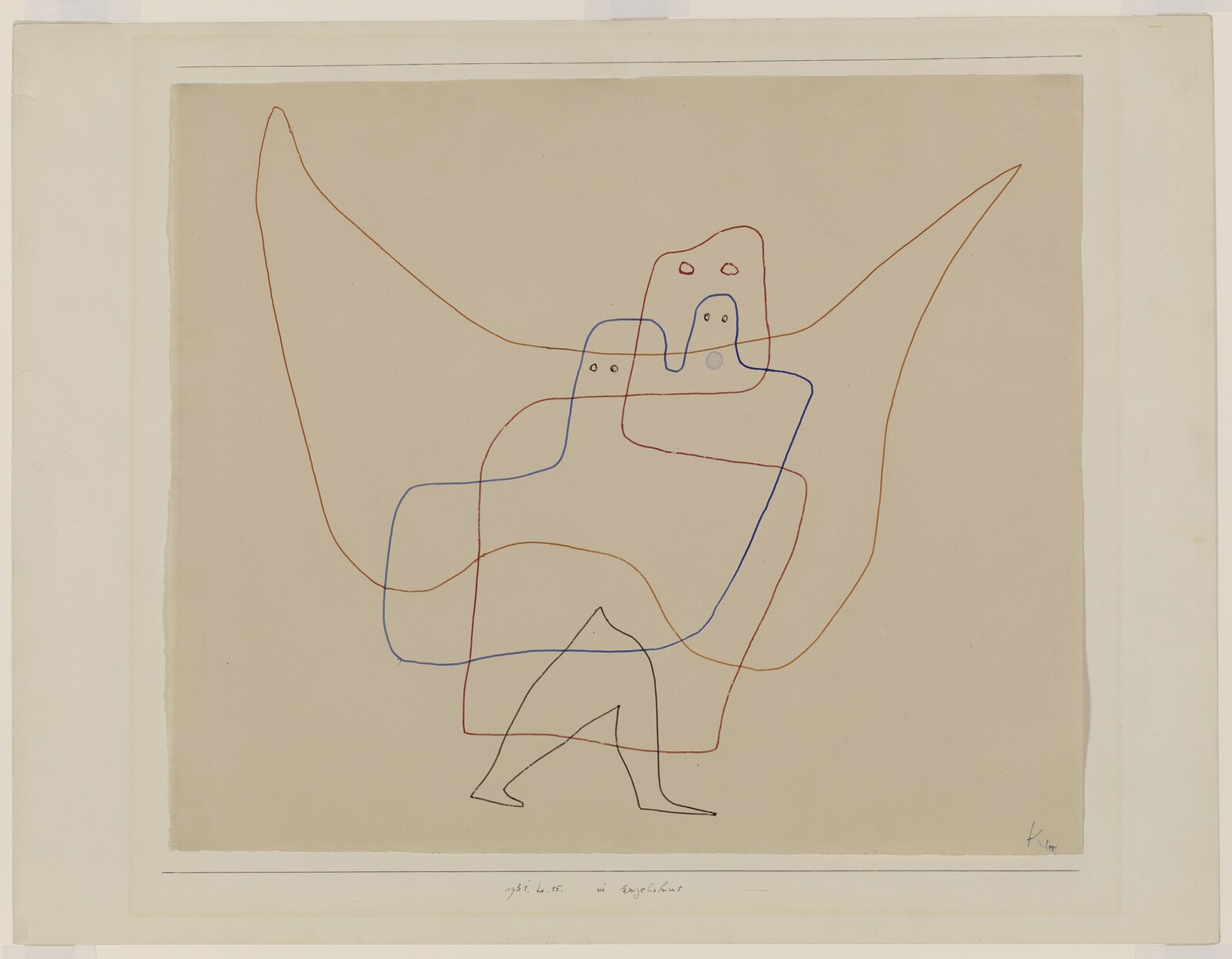

Rather than seeking out works of art that reinforce the dominant narrative of the present, the art historian—and his short-sighted accomplice, the critic—might instead be on the lookout for those that resist classification, that cannot be systematized, that are irrepressible because they are vital (Warburg called these recurring figures nachleben, or “afterlives”). And for those disorderly, chaotic, and dangerous irruptions of unstructured feeling that might explain the dissolution of old certainties and offer a glimpse of what is to come.

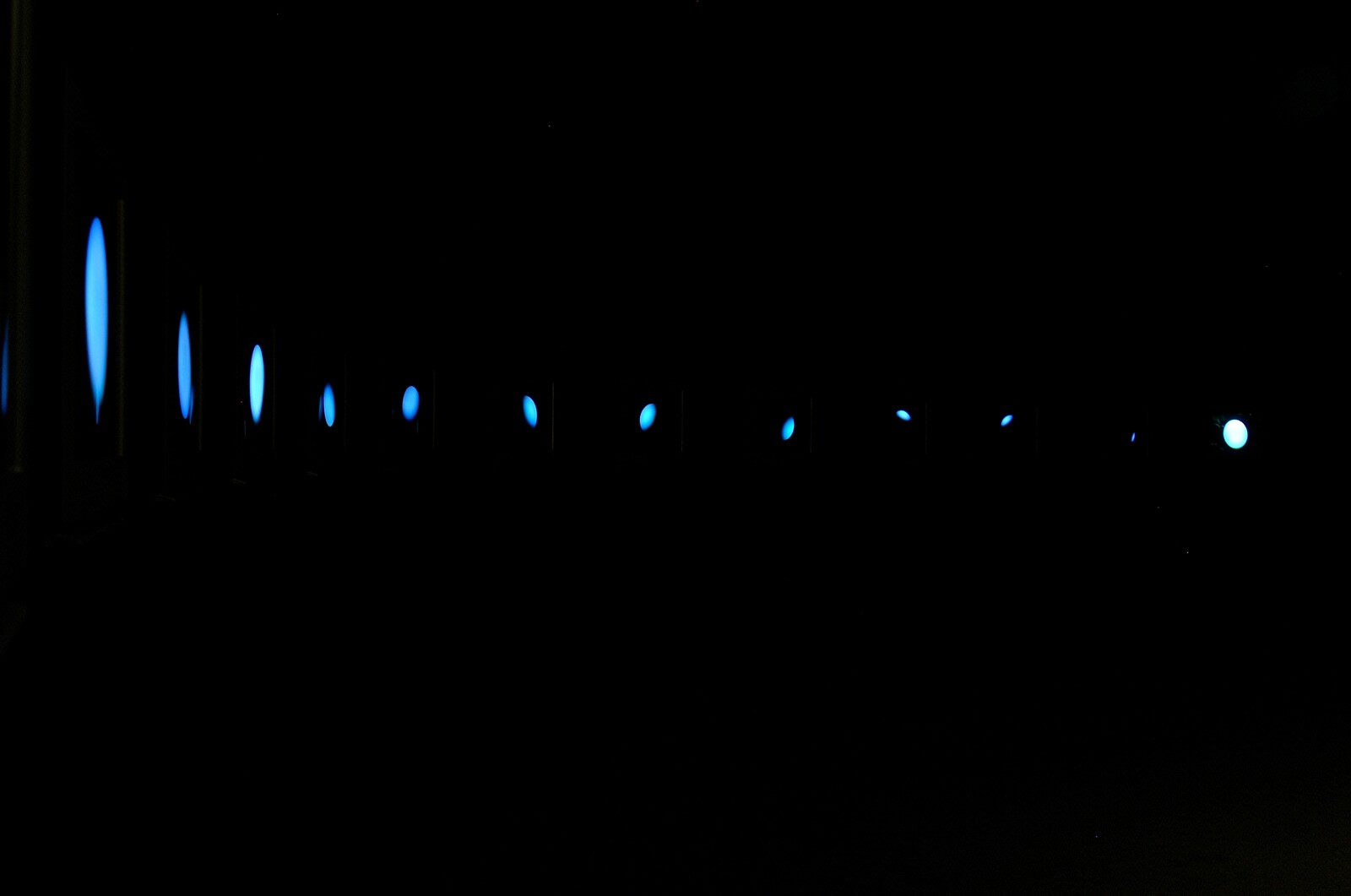

Fabric Object II